The Making Of: Pathways Into Darkness

by Tuncer Deniz

This month we'd like to start a new feature called The Making Of, that will occasionally appear in Inside Mac Games. We chose Pathways Into Darkness as our first The Making Of because of its fame as the first real-time texture mapping game on the Macintosh.

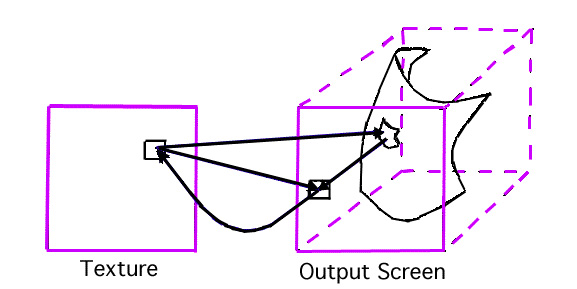

Now you've probably heard of texture mapping and know what it looks like, but what exactly is it? Texture mapping is a technique used to add visual detail to synthetic images in computer images. In the picture below, a texture plane is transformed onto a 3D surface and then projected onto the output screen (i.e., your monitor). Simple, huh?

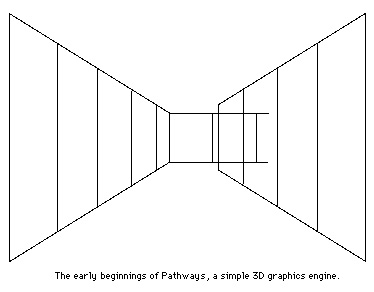

Jason Jones, programmer extraordinaire, got the idea to create Pathways Into Darkness when he first saw Wolfenstein 3D on a PC in the summer of 1992 while living in the dorms at the University of Chicago. Jones knew it wouldn't be easy, but realized the Mac was capable of doing full-motion, texture mapping. After gathering some ideas, Jones programmed a 3D graphic engine on the Mac that simulated halls and walls using simple wireframe-like rectangles and trapezoids. Although the graphic engine was crude and simple, it laid the foundation of the program.

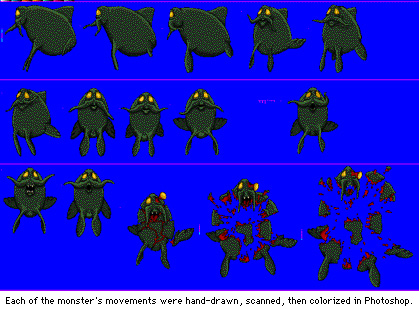

For the next few months, Jones and company worked on a improving and modifying the graphics engine until late 1992. In January 1993, the storyline was created and work began in earnest on the game. The plan was to ship the game in June or July, but as the months passed, their goal became to ship Pathways at Macworld Expo held in early August. While Jones worked on the interface and the graphics engine, artist Colin Brent hand-drew the monsters that would appear in the game.

Each monster had to be drawn in three different states: stationary, moving (walking or flying), and exploding. After the monsters, walls, guns, and other objects were added, then they were all scanned into the computer. The monsters (in black and white) were then put into the Pathways program to see if their motions looked lifelike. If they looked funny walking or exploding, they were re-drawn again until they "felt" right. After this stage, the monsters and other objects were meticulously colorized in Photoshop in 24-bit color.

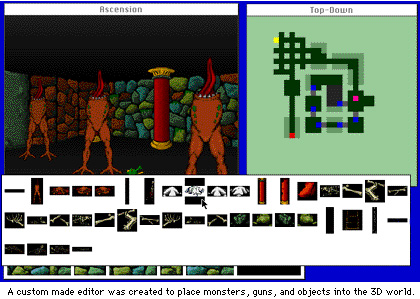

While the artist worked on fine-tuning the monsters, Jones created an editor for the game. The editor allowed Jones to place walls, doors, guns, monsters, and other objects onto each level. If it wasn't for the custom-made editor, it's safe to say that Pathways would probably still be in development.

As Jones and Brent worked on the game, Jones' partner Alexander Seropian worked on the games manual, box, marketing, and general hype (like the IMG preview).

By July, only the pyramid was finished, but all the levels underground remained to be created. The game was behind schedule and the pressure was on to ship by Macworld. Jones worked feverishly putting in 18 hour days, and rumor has it that Jones suffered a nervous breakdown (I'm just kidding). By the end of July most of the game was finished, and went into beta about a week before the Expo. Just before leaving for Macworld, 500 copies of Pathways were duplicated and shrinkwrapped in the offices of Bungie Software for sale at the show. Despite the rush at the end, the program came out relatively bug-free, thanks to Jones' careful programming.

The folks at Bungie are now working on two new products, one code-named Marathon, and the other one code-named Mosaic. Both products promise higher speeds on slower machines, and even more action than Pathways Into Darkness. Look for them in 1994.

© Inside Mac Games

All Rights Reserved.

Back to the Pathways Into Darkness page.